Scandinavian Herring Gulls wintering in Britain

Coulson, J. C., Monaghan, P., Butterfield, J. E. L., Duncan, N., Ensor, K., Shedden, C. and Thomas, C.

Ornis Scand. 15: 79-88.Biometric information was obtained from 13000 Herring Gulls Larus argentatus caught and ringed in northern England and southern Scotland outside the breeding season between 1978 and 1983. Morphological differences between males and females and between British and Scandinavian Herring Gulls have been used to identify both the sex and race of the birds. We describe the wintering distribution of the Scandinavian birds in Britain, their age and sex ratios and their time of arrival in and departure from Britain. Scandinavian Herring Gulls start to arrive in Britain in small numbers in September. The proportion of Scandinavian birds increases to a peak in December- January and the birds depart abruptly in late January or early February. Very few Scandinavian Gulls penetrate to the west side of Britain, while on the east side there is considerable regional variation in the proportion of Scandinavian birds. Between 70% and 80% of the adult Scandinavian birds examined were female. The proportion of adults amongst Scandinavian birds was much higher than amongst British birds.

J. C. Coulson, J. E. L. Butterfield, N. Duncan, C. Thomas, Dept of Zoology, Univ. of Durham, South Road, Durham DHI 3LE, UK.

P. Monaghan, K. Ensor, C. Shedden, Dept of Zoology, Univ. of Glasgow, Glasgow G12 8QQ, Scotland, UK.

1. Introduction

Bird species which breed over a wide climatic range often show geographical variation in their migratory behaviour; individuals breeding in the more hospitable parts of the species range are sedentary, while those subject to rigorous climatic conditions overwinter far from the breeding grounds. The Herring Gull Larus argentatus is such a species. The British birds are largely resident, in that there is no general shift of the population from the British Isles during the winter months and, while seasonal movements within Britain do take place (Coulson et al. 1982), movements over 300 km are rare (Thomson 1925, Poulding 1954, Harris 1964, Parsons and Duncan 1978). The Herring Gulls breeding in the northern region of Norway and the Murmansk region of USSR, on the other hand, undertake comparatively long distance winter migrations. Moreover, ringing studies have demonstrated that the northern Norway population mainly overwinters in areas to the south of those frequented by more southerly breeding Norwegian birds (Olsson 1958, Monaghan, unpubl.). The milder, maritime climate of Britain provides suitable overwintering conditions for these northern breeding birds and the indigenous British Herring Gull population is joined in winter by numbers of Herring Gulls which breed in the most northern areas of Europe. Most studies of the behaviour and ecology of the Herring Gull have concentrated on its breeding biology and comparatively little is known of the period outside the breeding season. The ringing studies mentioned above have tended to concentrate upon the post-breeding movements of Herring Gulls from a particular colony or area, as indicated by the recoveries of dead birds. The origin of the Herring Gulls wintering in a particular place, and the interactions of birds from different breeding areas have been little studied. There are morphological differences between British and Scandinavian breeding Herring Gulls which have warranted their division into separate sub-species. The nominate L. a. argentatus, the larger and darker of the two, breeds in Scandinavia and NW Russia while L. argentatus argenteus breeds further south including Britain (Barth 1964, 1966, 1967, 1968, 1975a, 1975b, Monaghan et al. 1983). We have used these morphological differences to identify the L. a. argentatus component of the wintering Herring Gulls in northern Britain and, using a large sample of individually marked birds, have made a study of the mixed populations. This paper reports on the identification of birds of Scandinavian and NW Russian origin and describes their distribution, age structure, sex-ratio and timing of arrival in and departure from northern Britain.

2. Methods

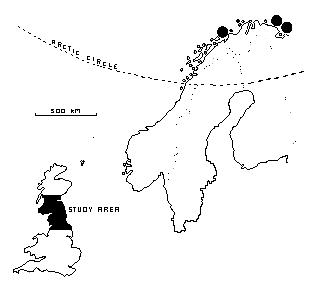

2.1. Sampling Herring GullsThe main study area was a large part of northern England and southern Scotland (shaded area in Fig. 1). The study was made in the five winters between 1978 and 1983. Samples of Herring Gulls were captured by cannon-nets at feeding sites, usually at refuse disposal tips. The average catch exceeded a hundred Herring Gulls and throughout the five years of this study over 15000 Herring Gulls were captured. More than 13000, caught outside the breeding season, were weighed and measured. All of the birds were ringed using B.T.O. numbered metal rings, and over 9000 were given a unique combination of colour-rings, allowing them to be identified as individuals in the field. Reservations -that catching exclusively at refuse tips might produce a biased sample were dispelled by the mobility of the birds and the fact that marked individuals fed not only at refuse tips but also at many other locations inland, on the coast and at sea. Work in progress demonstrates that, on average, tips are used on less than two days in each week by individual birds. Throughout this paper we refer to "Scandinavian" birds since this region covers the area from which we have had foreign recoveries in the breeding season (Fig. 1), although it is very likely that some birds from NW Russia are also involved (see Sect. 3.1).

Fig. 1. The location of all foreign breeding season sightings and recoveries of Herring Gulls ringed during the winter months in the main study area in Britain (shaded). Small dots represent single birds, large dots represent five birds.

2.2. Measurements

The following measurements were taken from each bird.

(a) Wing length. This was taken by the standard method involving the maximum length to the nearest mm after straightening the primaries.

(b) Bill depth. This was measured to the nearest 0.1 mm at the gonys with the beak held closed.

(c) Bill length. This was taken from the base of the culmen to the tip of the bill. However, this was found to be an unreliable measurement with a low level of reproducibility by different persons. In 1979, this measurement was replaced by head and bill length.

(d) Head and bill length. This is the length, measured to the nearest mm, from the back of the cranium to the tip of the bill. The method and its use in sexing birds has been reported by Coulson et al. (1983b). While head and bill length was found to be the most accurate measure of sex in a single population, this is not the case when populations are mixed (see Method 1, Sect 2.3). Head and bill length does, however, give the highest correlation with wing length of any of the measurements taken (r=0.76, n=743). It has, therefore, been used as a substitute for wing length in birds which were missing the longest primaries (either through moult or damage), using the relationship: estimated wing length=239.25 + 1.56(head and bill length).

(e) Weight. Each bird was weighed either on a direct reading balance to the nearest g or on a spring balance to the nearest 10g.

(f) Plumage. Several aspects of the wing tip pattern were recorded (see Coulson et al. 1982). In particular, the presence or absence of the thayeri pattern on the 9th primary (see Barth 1968) was recorded. This pattern is characterised by the grey area on the hind margin of the 9th primary extending, uninterrupted by black pigment, into the white "mirror" at the end of the feather. It has been recorded once only from the British population but occurs in up to 27% of the Herring Gulls breeding in northern Scandinavia (Barth 1968). Examination of 59 skins of Herring Gulls from NW Russia in the Zoological Museums of Lenningrad and Moscow Universities confirms that these birds also have a high proportion of individuals (27%) showing the thayeri character. This therefore gives a further character by which the area of origin of some individual birds caught in Britain could be determined and we used these as part of the sample of "Scandinavian" birds in the discrimination analysis.

(g) Leg colour. We examined the leg colour of all Herring Gulls captured. There has recently been a series of records of 'yellow-legged' Herring Gulls in Britain and in the southern part of the North Sea (Grant 1983, Devillers 1983). We found no Herring Gulls with yellow legs throughout the study. Thus we were not involved with Herring Gulls from the east Baltic or those from southern France and Iberia.

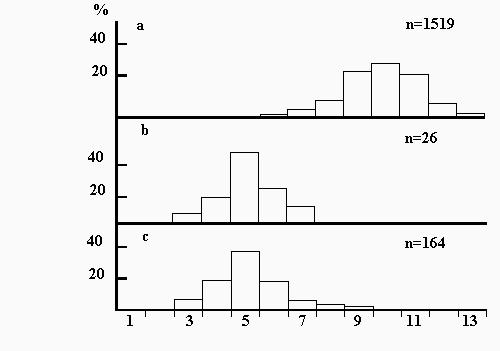

(h) Mantle shade. During the first year of the study, we became aware of the darker grey on the mantle of Herring Gulls which possessed the thayeri wing pattern and also in those which were larger than British breeding birds (including a Norwegian ringed adult). Since 1980, we have used a 13 shade reference strip covering the range of grey found on the mantle of Herring Gulls we captured. This offered a greater series of intermediate shades than that in commercial colour and shade charts (e.g. Munsell charts). The shades were produced by exposing matt photographic paper for progressively longer periods and developing the papers until no further change took place. The shades were numbered 1-13 (dark to light) and corresponded (approximately linearly) to the Munsell range N4.5 to N7.5. Our Munsell values for northern Scandinavian Herring Gulls agreed closely with those obtained by Barth (1966) using a reflectometer. We found higher (that is paler) shades than he did for British birds, but his results came from a very small sample of British birds taken in the extreme north of the country. The distributions of mantle shades for birds with the thayeri wing tip pattern and for birds caught in Britain and subsequently seen or recovered in northern Scandinavia are shown in Fig. 2. These distributions are similar but the figure also presents the shade distribution of British breeding birds and it is evident that there is very little overlap between these and Scandinavian birds.

(i) Ageing. All birds were aged by plumage into four immature year classes and an unaged, adult class (see Witherby et al. (1945) and Grant (1982) for details). We employed the convention that the immature age classes changed on 1 July each year.

2.3. Separation of British and Scandinavian Herring Gulls using body measurements

Two different methods were used to separate Herring Gulls according to their sex and race. Both made use of the SPSS discrimination analysis programme DISCRIMINANT (Nie et al. 1975).

Fig. 2. The percentage distribution of the shade of the grey mantle of Herring Gulls on an arbitrary scale of 1-13 covering the Munsell range N4.5 to N7.5. Adults: (a) from British breeding colonies. (b) ringed in Britain during the winter months and subsequently found in breeding colonies in north Norway. (c) which possess the thayeri wing pattern characteristic of Scandinavian birds (see text). Note the high degree of separation between British and Scandinavian birds which makes this morphometric feature a good indicator of race in this species.

Method 1

This method makes use of two measures of body size and each bird is assigned to one of four categories: British male, British female, Scandinavian male and Scandinavian female. The most appropriate body measurements were selected on the basis of a comparison between samples of adult Herring Gulls from breeding colonies in north Norway (Barth 1967 and C. Johnson, unpubl. Ph.D. thesis) and northern Britain which had been sexed by dissection. Bill depth was found to be the best method of sexing live individuals from mixed populations of British and Scandinavian birds since it differed least between the two races and had a high degree of separation between the sexes. Bill depth increases with age so, for birds of four years or less, the bill depth measurement was corrected to that expected when it becomes a seven year old adult, using the relationship between bill depth and age reported by Coulson et al. (1981).

The races were separated using wing length but when the longest primaries were in moult or not fully grown, wing length was estimated from the head and bill measurement as described above.

When we first developed Method 1, we expected that it would separate correctly about 95% of the birds. However, despite correcting bill depth for age, the degree of overlap between the biometrics of birds from the two populations was greater than we had envisaged. In fact the accuracy of the method, measured by testing it on an independent sample of 220 birds from the British breeding population revealed that 40 (18%) of the birds were mis-identified. Clearly, the origin of all individual birds could not be identified with confidence using this method. However, after a correction was applied for this error, Method 1 still allowed us to obtain realistic estimates of the proportion of Scandinavian Herring Gulls in our catches. This was done in the following way. Samples with less than 18% of the birds classified as Scandinavian were considered to be composed entirely of British birds; catches with greater than 18% of birds classified as Scandinavian had the proportion corrected using the relationship:

where y is the corrected percentage of Scandinavian birds and x is percentage obtained by Method 1. This relationship corrected catches with up to 50% Scandinavian birds in them and none of our catches exceeded this level. The correction allows for an 18% error in the identification of both British and Scandinavian birds. At 50% of each the errors cancel each other out.

Examination of the independent sample of 220 Herring Gulls known to belong to the British breeding population, and for which measurements of both head and bill and wing length were available, revealed that the error increased to 30% when head and bill length was used to estimate wing length. The October catches, when many birds lacked the longest primary and where wing length has been estimated using head and bill length, have been corrected for this 30% error.

Method 2

This method makes use of the mantle shade of the birds over two years old, in addition to the body size measurements, to predict whether or not the bird belongs to the British or Scandinavian race. Since there is a high degree of separation of the two races using mantle shade (Fig. 2), we were able to classify correctly all of the individuals in the sample of 220 Herring Gulls from the British population and in the samples used in the discriminant analysis 98% were correctly identified.

Application of both Method 1 and 2 to the same samples gave very similar estimates of the proportion of Scandinavian birds thus validating the way in which the Method 1 estimates were corrected. Method 1 was used on all first and second year birds throughout the study(since they lack extensive grey mantle plumage), and on birds aged over two years in 1978 and 1979, before mantle shade was recorded. From 1980 Method 2 was used on all samples of birds over two years old.

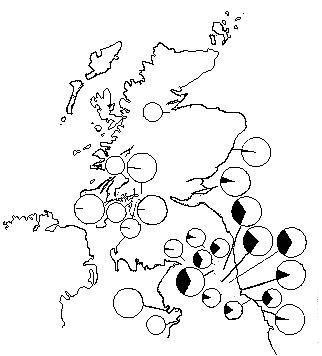

The proportions of wintering Herring Gulls of Scandinavian origin were estimated for three age groups (lst year, 2-4 years old and adult) in the eastern and western halves of the study area. The main catching localities are shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. The proportion of adult Herring Gulls caught between November and January at different localities in Britain which were identified as Scandinavian (black sectors). Note that very few Scandinavian birds penetrate to the west side of Britain and on the east side there is considerable regional variation. Small circles represent samples of between 30 and 99 adult birds: large circles represent samples greater than 99. The sample sizes at each site are given in the Appendix.

3. Results

3.1. Area of origin of the Scandinavian Herring Gulls

Breeding season sightings and ringing recoveries of Scandinavian Herring Gulls marked during this study are shown in Fig. 1. The great majority of these foreign sightings and recoveries were within the Arctic Circle, with none outside Norway. These results are consistent with our finding that a high proportion of the wintering Scandinavian Herring Gulls in east Britain have the thayeri wing pattern (Tab. 1, last line). Several of the recovery sites shown in Fig. 1 are within 100 km of the Russian border and Tatarinkova (1970) has shown that some Herring Gulls ringed in NW Russia overwinter in eastern Britain. It is therefore very likely that some of the birds which we identified as Scandinavian breed in NW Russia, particularly since these birds also have a high proportion with the thayeri wing pattern. However, we have not received any recoveries or sightings from Russia.

3.2. Geographical distribution of Scandinavian Herring Gulls within the study area

Tab. 1. The timing of capture in eastern Britain of Herring Gulls known to breed in Scandinavia (A) and with the thayeri wing pattern (B) compared with that of the birds we have identified as Scandinavian (E). Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Jan Feb A. No. of marked birds seen or recovered in Scandinavia during the breeding season O 1 1 10 7 18 2 B. No. of thayeri individuals caught O 1 (4)** 42 50 59 26 C.* Total no. of known Scandinavian birds caught 0 2 5 50 55 71 27 D. Total no. of adults caught 206 676 408 755 720 1365 483 E. Total no. of adults identified as Scandinavian (from Tab. 3) 0 5 (41) 164 196 344 100 % known Scandinavian (C. 100/D) 0 0.3 1.2 6.6 7.6 5.2 5.6 % Scandinavian with thayeri pattern (B. 100/E)- - 20 (10) 26 26 17 26 * 9 birds where the thayeri wing pattern had been noted were later seen in Scandinavia so line C=A+B-9. ** Figures for October are given in brackets since primary moult at this time prevents identification of wing pattern in a number of birds.

The proportion of adult Scandinavian birds captured in the three months, November, December and January in each of the four winters of the study at the main sites in NE England are shown in Tab. 2. There is no significant difference between winters and we have combined data from all years when considering the geographical distribution and timing of arrival of the Scandinavian birds. Tab. 3 shows the proportion of adult Scandinavian Herring Gulls in catches made in the eastern and western halves of the study area in each month between August and April. It is evident that few adult Scandinavian birds penetrate to the west side of Britain and Fig. 3 shows this clearly in the November to January period. This finding is also supported by the presence of only one adult with a thayeri wing pattern among more than 3000 adults caught outside the breeding season on the west side of Britain. The situation on the east side contrasts markedly with this; on occasion, over 10% of the adult Herring Gulls in catches had the thayeri wing pattern. Fig. 3 also shows the variation in proportions which occurs in eastern Britain. One area, encompassing Tyne and Wear, Co. Durham and Cleveland has a high proportion of Scandinavian Herring Gulls. Based on an estimate of 15000 adult Herring Gulls wintering in this area, there are some 3600 Scandinavian adults present each winter. On the other hand, there is a much lower proportion of adult Scandinavian Herring Gulls overwintering in eastern Scotland and the Scarborough area of Yorkshire (Fig. 3). A summary of the catches at each site, showing the samples sizes, is given in the Appendix.

Tab. 2. The proportion of adult Herring Gulls caught at the main study sites m NE England during November, December and January in each winter which were of Scandinavian origin.

Winter Sample No. of Percentage size Scandinavian Scandinavian birds 1978-1979 393 116 29.5 1979-1980 622 201 32 3 1980-1981 432 134 31 0 1981-1982 447 146 32.7The proportion of Scandinavian Herring Gulls among the 2-4yr old birds (Tab. 4) and the first years (Tab. 5) were also higher in the east coast catches but the levels are much lower than those for adults.

Tab. 3. The proportion of adult Herring Gulls caught in east and west Britain, outside the breeding season, which were identified as Scandinavian. Data have been pooled for the four years of the study.

East Britain West Britain n No. of % n No. of % Scandinavian Scandinavian Scandinavian Scandinavian Aug .................... 206 0 0.0 46 0 0.0 Sep .................... 676 5 0.7 103 0 0.0 Oct .................... 408 (41) (10.0) 430 0 0.0 Nov .................... 755 164 21.7 480 2 0.4 Dec .................... 720 196 27.2 325 5 1.5 Jan .................... 1365 344 25.2 736 3 0.4 Feb .................... 483 100 20.7 177 1 0.6 Mar .................... 10 2 20.0 357 0 0.0 Apr .................... 1 0 0.0 381 0 0.0

Figures for October are given in brackets since, due to the absence of a wing length measurement for Herring Gulls caught at this time in primary feather moult, these figures are likely to be less accurate.

Tab. 4. The proportion of 2-4yr old Herring Gulls caught in east and west Britain, outside the breeding season, which were identified as Scandinavian. Data have been pooled for the four years of the study.

East Britain West Britain n No. of % n No. of % Scandinavian Scandinavian Scandinavian Scandinavian Aug .................... 81 0 0.0 35 0 0.0 Sep .................... 226 0 0.0 46 0 0.0 Oct .................... 296 (14) (4.7) 146 0 0.0 Nov .................... 169 20 11.8 145 2 1.4 Dec .................... 172 28 16.3 119 4 3.4 Jan .................... 366 58 15.8 111 2 1.8 Feb .................... 226 14 6.2 86 0 0.0 Mar .................... 37 0 0.0 97 0 0.0 Apr .................... - - - 148 0 0.0

Figures for October are given in brackets since, due to the absence of a wing length measurement for Herring Gulls caught at this time in primary feather moult, these figures are likely to be less accurate.

3.3. Timing of arrival and departure of Scandinavian Herring Gulls in northern Britain

The period of arrival of Scandinavian Herring Gulls in Britain is protracted. Examination of the proportions of adult Scandinavian Herring Gulls caught in different months suggests that they begin to arrive in small numbers as early as September (confirmed by a ringing recovery). The proportion of Scandinavian adults increases over the next three months, reaching a peak in December when they form 27% of the adult catch (Tab. 3) and 18% of the total catch. The Scandinavian first year birds found in August and September have probably been misidentified (because of the magnitude of the correction required to convert the bill depth to adult dimensions) as there are no other indications that first year Scandinavian birds arrive before October (Olsson 1958, Tatarinkova 1970). If these early records are accepted as errors, the first year Scandinavian Herring Gulls appear to arrive later than the adults, with no birds recorded in October and only four (2% of the Scandinavian birds caught) in November. The proportion of first years amongst the Scandinavians increases to 10% in December but declines in January and none were caught in February (Tab. 6) or March. The 2yr old birds appear to arrive and depart at the same time as the adults. We have not caught any Scandinavian Herring Gulls during the summer but there is some evidence from both Russian (Tatarinkova 1970) and Norwegian ringing that a few immature birds may summer in Britain.

The protracted pattern of arrival of Scandinavian Herring Gulls is confirmed by the captures of birds with a thayeri wing pattern and birds which were marked on capture and were later seen or recovered in Scandinavia during the breeding season (Tab. 1). The timing of capture of these birds also shows that they do not arrive in Britain in large numbers until November. The proportion of the identified Scandinavian adults which had a thayeri wing pattern remained approximately constant at about 22% between September and February (Tab. 1). This proportion of thayeri adults is similar to the values of 21-27% reported by Barth (1968) for northern Norway and to our own finding of 27% thayeri among birds taken in NW Russia. The dates of sightings in Britain of Herring Gulls known to breed in Norway are shown in Tab. 7. Since the timing of capture will influence the distribution of sightings in the same winter, these results relate only to winters subsequent to that in which the bird was first marked. A similar pattern to that reported above emerges; the majority of Scandinavian Herring Gulls do not arrive in Britain until late autumn and maximum numbers are present in January. Most of the birds which have been breeding in north Norway leave Britain in late January and February (Tab. 7) and by March there are no Scandinavian birds remaining in the study area. Our field observations suggest that the departure in February is abrupt with most of the birds departing within 3 or 4 days.

Tab. 5. The proportion of 1yr Herring Gulls caught in east and west Britain, outside the breeding season, which were identified as Scandinavian. Data have been pooled for the four years of the study.

East Britain West Britain n No. of % n No. of % Scandinavian Scandinavian Scandinavian Scandinavian Aug..................... 38 1 2.6 65 1 1.5 Sep..................... 162 2 1.2 174 3 1.7 Oct..................... 597 0 0.0 258 1 0.3 Nov..................... 242 4 1.7 227 1 0.4 Dec..................... 221 24 10.9 105 1 1.0 Jan..................... 213 29 13.6 106 1 0.9 Feb..................... 181 0 0.0 113 2 1.8 Mar..................... 59 0 0.0 106 1 0.9 Apr ..................... - - - 101 0 0.0

Tab. 6. The age composition of the Herring Gulls identified as British (Brit.) and Scandinavian (Scan.) for catches in NE England during the non-breeding season. Data have been pooled for the four years of the study. Differences between British and Scandinavian Herring Gulls in age composition are significant for all months (P < 0.01 in all cases). Figures in brackets are percentages of the total for each race. (There are insufficient Scandinavian birds in September for a meaningful comparison.)

Sep Oct Nov Dec Jan Feb Totals

Brit. Scan. Brit. Scan. Brit. Scan. Brit. Scan. Brit. Scan. Brit. Scan. Brit. Scan.

No. adult...... 671 5 367 41 591 164 524 196 1021 344 383 100 3557 850

(64) (71) (30) (75) (60) (87) (61) (79) (68) (80) (50) (88) (55) (81)

No. 2-4 yr old..226 0 272 14 149 20 144 28 308 58 212 14 1311 134

(21) (0) (22) (25) (15) (11) (17) (11) (20) (13) (27) (12) (20) (13)

No. 1 yr old... 160 2 597 0 238 4 197 24 184 29 181 0 1557 59

(15) (29) (48) (25) (2) (22) (10) (12) (7) (23) (24) (5.6)

X2 - 69.4 57.2 30.4 24.7 62.4

3.4. Sex ratio of Scandinavian Herring Gulls

In a sample of 178 adult Herring Gulls showing the thayeri wing tip pattern, 146 (82%) were identified as females from their biometrics. Similarly, of 213 adult birds with a mantle shade of less than 6 on our scale (the range in which there is little likelihood of British birds being included). 71% were female. Clearly, there is a marked inequality in the sex-ratio of adult Scandinavian Herring Gulls wintering in NE Britain. The mean wing length of the 178 thayeri birds was 441 mm which is similar to the mean wing-length of Scandinavian birds recorded in the London area by Stanley et al. (1981). Presumably their sample was also biased in favour of females.

3.5. Age composition of Scandinavian Herring Gulls

Tab. 6 gives the age structure of the Scandinavian and British Herring Gulls caught in NE Britain each month. Overall a much higher proportion (81%) of the Scandinavian birds was adult, compared to British birds (55%), with higher proportions of adults occurring among the Scandinavian birds in all months that they were present in appreciable numbers.

Tab. 7. The timing of sightings in Britain in the years subsequent to capture of 20 individually marked Herring Gulls known to breed in north Norway. The first line gives the total number of sightings of these birds within the study area in each month. The patterns of first and last sightings of each bird in each winter are given in lines 2 and 3, respectively. Taking the first sighting to indicate arrival and the last departure, line 4 shows the number of these birds remaining in the study area in each month.

Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Jan Feb Mar

Total sightings 0 4 12 38 38 74 29 0

First sightings 0 2 8 10 8 8 1 0

Last sightings 0 0 0 3 6 15 13 0

No. remaining 0 2 10 20 25 27 13 0

3.6. Field identification of Larus a. argentatus and L. argentatus argenteus

Recently, considerable interest has built up in the possibility of identifying the area of origin of Herring Gulls visiting Britain using field observations (Hume 1978). Since we have had many birds which were examined in the hand, measured for mantle shade and size and then subsequently seen in the field, we are in a position to comment on the identification of northern Scandinavian birds under field conditions.

Firstly, the lighting conditions vary the extent to which isolated individuals appear to have a light or dark mantle and without other birds for comparison, we would place very little confidence on such identifications. In fact we note that Morley (1979) did not detect the shade difference in north Norwegian Herring Gulls which she caught at the breeding sites, nor did Stanley et al. (1981) note the darker shade, presumably because of the lack of British birds for comparison. Even when British Herring Gulls were available for comparison, we found it difficult and often impossible to identify northern Scandinavian Herring Gulls in the field on days with bright winter sunshine. The task was somewhat easier with total cloud cover, when the amount of incoming light was reduced. Further we warn against the apparent change in shade arising from the position of the bird in relation to the observer; on several occasions apparently dark plumaged birds became light. It is not usually possible to recognise the thayeri wing pattern in the field. In general, the northern Scandinavian birds show less black pigment on the wing tips and almost invariably have a long white tip to the 10th (outer) primary which can be noted if the wing is opened, for example, during an aggressive encounter. Note, however, that an appreciable minority of British birds, particularly those from NE Scotland, also show this character. The shortage of Scandinavian males wintering in NE England also means that size is of use in only a minority of cases. In our view, a very large Herring Gull with dark grey wings and mantle and with reduced black pigment and more extensive white markings on the wing tip is almost certainly a bird from Scandinavia or NW Russia. In the majority of cases, however, the identification can only be satisfactorily made with the bird in the hand and with suitable reference shades available for comparison.

4. Discussion

Ringing studies have shown that the continental Herring Gulls which visit northern Britain during the winter months originate mainly in arctic Norway and NW Russia (Olsson 1958, Tatarinkova 1970, present study). We have found that the Scandinavian birds which reach Britain winter almost exclusively on the eastern side of the country where, in places, they form about 30% of the wintering Herring Gulls. The failure of the Scandinavian birds to penetrate in any numbers to the western coast of Britain is surprising, considering the distance they have travelled to reach Britain in the first place. We have evidence (unpubl.) that British Herring Gulls are equally unwilling to move E to W across England and Scotland and that narrow stretches of land (less than 120 km in places) act as a considerable barrier. Scandinavian birds concentrate in certain areas within our study area in eastern Britain. For example, higher proportions of these birds have been found in NE England between the River Tyne and the north of Yorkshire, than in areas to the north or south. This may arise from the small numbers of resident breeding birds in this area which, presumably, dilute the proportion of the Scandinavian Herring Gulls elsewhere. Alternatively, the local birds may have a competitive advantage and force the Scandinavian birds into areas where the density of other Herring Gulls is relatively low. Stanley et al. (1981) reported the exclusive use of areas in SE England by Scandinavian Herring Gulls but we have found no such examples in northern Britain, indeed the Scandinavian birds were always in the minority.

The arrival of the Scandinavian gulls in our study area is spread over a 5-month period, September to January, but few birds arrive before mid October. The peak of arrivals in the November-early January period is late compared with the arrival of other gull species from Scandinavia (Radford 1960,1962, Coulson et al. 1984). Thus most of the adults arrive after primary moult is almost complete, but the moult is unlikely to be the cause of the late arrival since the first year birds, which do not moult, and older immature birds, which moult earlier (Walters 1978, Coulson et al. 1983a), arrive at the same time as the adults. The late arrival of the Scandinavian birds contrasts with the earlier arrival of the British breeding birds, many of which are departing from NE England for their breeding areas as the Scandinavian birds are arriving. This will be discussed further in another paper.

Most of the Scandinavian birds depart during January and in the first half of February. The exit in February is synchronised and most of the birds depart in the same 3 or 4 days. A similar abrupt departure also occurs in the Norwegian Great Black-backed Gulls which winter in NE England (Coulson et al. 1984). Some sighting and ringing recoveries of adult Herring Gulls in northern Norway suggest that these abrupt departures involve a rapid and probably direct movement back to the breeding area. Our observations were based predominantly on females and we have insufficient data to determine if, on average, males depart at a different time to females. It would be interesting to know whether Scandinavian birds, in particular those wintering on the continental coast of the North Sea, depart at the same time.

Throughout the winter period, the proportion of adult and immature Scandinavian Herring Gulls differs markedly from the proportion in the British samples. It is possible that the low proportion of immature Scandinavian birds stems from these young birds moving shorter distances from their natal areas. This is not supported by either the Norwegian or the Russian ringing recoveries (Tatarinkova 1979). An alternative possibility, that the breeding success in northern Scandinavia is lower than that in Britain, is more likely. There is support for this latter explanation in that there are reports of low breeding success in Norway (Folkestad 1978, Johansen 1978) and this is probably the situation in northern Scandinavia as a whole. A similar low proportion of immature birds has been found among Norwegian Great Black-backed Gulls wintering in NE England has also been attributed to poor breeding success (Coulson et al. 1984).

The differences in size and colour of the Scandinavian Herring Gulls as compared with British birds are in marked contrast to the situation in the Great Black- backed Gull where British birds are the same size (and shade) as those breeding in northern Scandinavia and NW Russia (Coulson et al. 1984). The reason for the appreciable difference in size of the Herring Gulls is not clear although the size change follows Bergmann's Rule with greater size occurring in the colder part of the animal's range. This suggests that the selection for size in this species takes place in the spring and summer when the populations are separated. If this explanation which has been put forward in general terms by Salomonsen (1955) is correct, then it would appear that the selection pressures on size in the Great Black-backed gull occurs in the wintering area and it is, perhaps, significant that many Great Black-backed Gulls move from Scandinavia to Britain at least two months earlier and remain there longer than the Herring Gulls.

Appendix. The numbers and proportions of Scandinavian birds amongst adult Herring Gulls caught at different localities in Britain during the months of November, December and January (1978-1983). These data are shown in Fig. 2.

Location County Number Number %

Caught Scandinavian Scandinavian

Scarborough North Yorkshire 208 15 7.2

Mickleby North Yorkshire 65 20 0.8

Loftus Cleveland 40 8 20.0

Darlington Durham 68 6 8.8

Hartlepool Cleveland 240 34 14.2

Wingate Durham 547 188 34.4

Coxhoe Durham 943 272 28.8

Chester-le-Street Durham 242 74 30.6

Consett Durham 149 48 32.2

Greenside Tyne and Wear 32 9 28.1

Prudhoe Northumberland 83 25 30.1

Hexham Northumberland 50 3 6.0

Kirkcaldy Fife 265 28 40.6

Aberdeen Grampian 113 4 3.5

Inverness Highland 86 0 0.0

Lochgilphead Strathclyde 68 0 0.0

Helensburgh Strathclyde 229 2 0.9

Croy Strathclyde 75 1 1.3

Bishopbriggs Strathclyde 556 2 0 4

East Kilbride Strathclyde 206 1 0.5

Irvine Strathclyde 49 0 0.0

Longtown Cumbria 42 1 2.4

Walney Cumbria 318 0 0.0

Lancaster Lancashire 37 0 0.0

Acknowledgements - The data used in this paper were collected with the help of a number of individuals from Durham and Glasgow Universities and we extend our thanks to them all. We wish to thank Christine Johnson (nee Morley) for supplying us with standard body measurements of sexed Herring Gulls collected in north Norway. We also wish to acknowledge the assistance given by Dr. R. Furness, N. Aebischer, S. Greig, K. Bayes, H. Wright, D. Hutchinson, J. Richardson, E. Henderson and M. Bone. Thanks are also due to staff of the Nature Conservancy Council, Royal Society for the Protection of Birds and Scarborough Council for their co-operation and assistance which enabled us to obtain biometric data from birds taken in breeding colony culls. This research would not have been possible without the continued goodwill and facilities provided by the executives and staff of a number of local authorities, in particular, Durham County Council and Strathclyde Regional Council. The study was financed by research grants from the Natural Environment Research Council.

References

Barth, E. K. 1964. Variation in the mantle colour of Larus argentatus and Larus fuscus: Preliminary report. Det Kongl. Norske Vidensk. Selsk. Forh. 37: 119-121. - 1966. Mantle colour as a taxonomic feature in Larus argentatus and Larus fuscus. - Nytt Mag. Zool. 13: 56-82. - 1967. Standard body measurements in Larus argentatus, L. fuscus, L. canus and L. marinus. - Nytt Mag. Zool. 14: 7-83. - 1968. The circumpolar systematics of Larus argentatus and Larus fuscus with special reference to the Norwegian populations. - Nytt Mag. Zool. 15, Suppl. 1: 1-50. - 1975a. Taxonomy of Larus argentatus and Larus fuscus in north-western Europe. - Ornis Scand. 6: 49-63. - 1975b. Moult and taxonomy of the Herring Gull Larus argentatus and the Lesser Black-backed Gull Larus fuscus in north-western Europe. - Ibis 117: 384-387. Coulson, J. C., Butterfield, J. E. L., Duncan, N., Kearsey, S., Monaghan, P. and Thomas, C. S. 1984. The origin and behaviour of Great Black-backed Gulls wintering in N.E England. - British Birds 77: 1-11. -, Duncan, N. Thomas, C. S. and Monaghan, P. 1981. A age-related difference in the bill depth of Herring Gulls Larus argentatus. - Ibis 123: 499-502. -, Monaghan, P., Butterfield J. E. L., Duncan, N., Shedden, C., and Thomas, C. S. 1983a. Seasonal changes in the Herring Gull in Britain: weight, moult and mortality. Ardea 7: 235-244. -, Monaghan, P., Butterfield, J. E. L., Duncan, N.. Thomas, C. S. and Wright, H. 1982. Variation in the wingtip pattern of the Herring Gull in Britain. - Bird Study 29: 111-120. -, Thomas, C. S., Butterfield, J. E. L., Duncan, N., Monaghan, P. M. and Shedden, C. 1983b. The use of head and bill length to sex live gulls (Laridae). - Ibis 125: 549 Devillers, P. 1983. Yellow-legged Herring Gulls on southern North Sea shores. - British Birds 76: 191- 192. Folkstead, A.O. 1978. Recent surveys and population changes of the seabird population of More & Romsdal. - Ibis 120: 121-122 Grant; P J. 1982. Gulls: a guide to identification. - Poyser, - 1983. Yellow-legged Herring Gulls in Britain. British Birds 76: 192-194 Harris, M.P. l964. Recoveries of ringed Herring Gulls. Bird Study 11: 183-191. Hume, R.A. 1978. Variation in Herring Gulls at a Midland roost. British Birds 71: 338-345. Johansen, O. 1978. Reproduction problems of some Laridae specles in western Norway. - Ibis 120: 114- 115. Monaghan, P., Coulson, J. C., Duncan, N., Furness, R W Shedden, C. and Thomas, C. S. 1983. The biometrics of Herring Gulls Larus argentatus in Britain and the geographical variaton in wing length in northern Europe. - Ibis 125: 412-417. Morley, C. 1979. Variations in Herring Gulls. - British Birds 72: 389-390. Nie, N.H., Hull, C.H., Jenkins, J.G., Steinbrenner, K. and Brent, D H. 1975. Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, 2nd edn. - McGraw-Hill. London. Olsson, V. 1958. Dispersal, migration, longevity and death causes of Strix aluco, Buteo buteo, Ardea cincerea and Larus argentatus. - Acta Vertebr. 1: 91-189. Parsons, J. and Duncan, N. 1978. Recoveries and dispersal of Herring Gulls from the Isle of May. J. Anim. Ecol. 47: 993-lOO5. Poulding, R. H. 1954. Some results of marking gulls on Steepholm. - Proc. Bristol Nat. Soc. 29: 49-56. Radford, M. C. 1960. Common Gull movements shown by ringing returns. - Bird Study 7: 81-93. - 1962. British ringing recoveries of the Black- headed Gull. - Bird Study 9: 42-55. Salomonsen, F. 1955. The evolutionary significance of bird migration. - Det Kongl. Danske Vidensk. Selsk. Biol. Medd. 22. Stanley, P. 1., Brough, T., Fletcher, M. R., Horton, N. and Rochard, J. B. A. 1982. The origins of Herring Gulls wintering inland in south-east England. - Bird Study 28: 123 132. Tatarinkova, 1. P. 1970. The results of ringing Great Black-backed and Herring Gulls in Murmansk. - Trudy Kandalakshskogo gos. zapovednika 8: 149-181. Thomson, A. L. 1925. The migrations of the Herring Gull and Lesser Black-backed Gull: results of the marking method. British Birds 18: 34-44. Walters, J. 1978. The primary moult in four gull species near Amsterdam. - Ardea 66: 32-47. Witherby, H. F., Jourdain, F. C. R., Tcehurst, N. F. and Tucker, B. W. 1945. The handbook of British Birds. Vol. 5. Witherby, London.